Decision Making

Stuart asked:

“How do you know if the decision you are making and the direction you are going when a problem occurs is the right one? Furthermore, how do you stop self doubts?”

That’s a good question and one that is not so simple to answer. Since a few of you had asked me this question in one form or another over the past year or so, I’ll combine Stuart’s question with a couple of others and try to answer.

Decision making is one of those things that can be taught, but really can’t be taught. Yeah, what you just read. What I mean is that you need equal parts of experience and training. Training gives you a good baseline, while experience lets you sort rapidly through many possible courses of action and select the most viable.

In how to deal with an emergency, I talked about the use of visualization as a way of planning if something goes wrong. By visualizing the different issues and what you’d do, your mind has a plan it can follow later if the crisis presents itself. So, use visualization as a form of training that can help creating baselines, a collection of guardrails, and priorities that can help us learn how to quickly take the reactions out of the equation and be more proactive.

To do so, imagine what can go wrong in the place you are. Be wild, go to the extreme. Really imagine the place on fire, or a shooter coming into the office building, or an earthquake. Work your imagination and try to see all the things as they unfold in front of you. Once you have that try to find how you would react to each one and what the preferable course of action would be. List those in your mind together with a secondary one, a plan B.

Next think about the things you will do in general during a crisis, and those you won’t; for example, you will not take the elevator if there is a fire in the building. Be realistic about what those things you will never do, they would help later.

You have now a list of things that you'd do during a crisis or problem, and you practice (in your mind) how you'd react to things going wrong. This is your baseline. These are the guardrails you put in place that help you make quick decisions under stress.

We mentioned priorities as part of that baseline. This is extremely important because it will help you remain safe in extreme cases. I know it’s a touchy subject, but prioritizing actions, especially when you are at risk, may call for leaving someone behind. For example, in case of an active shooter in the building, you need to run and escape, grabbing whoever you find along the way to go with you and take them to safety, so you can call law enforcement. However, if trying to save people will cause your escape to fail, well, sometimes you will need to just leave them behind, prioritizing your own safety. People will do the same for themselves, so you have to be prepared.

It’s a bad situation to be in, but then again, we are talking about decision making. Develop the situation because each one will be somewhat different.

Speaking of developing the situation, another thing we saw in the article about how to deal with an emergency is the need to pause one second to really understand what’s going on and give you the chance to make a better, less rushed, decision.

I learned a mantra many years ago: stop, take a breath, understand, make a decision. I repeat that whenever things get hectic, it helps slow things down so I can make better decisions. If you combine this with situational awareness, then you can really begin to develop the situation as it unfolds. If you have the baselines and guardrails in place, then you can loop through the possible decisions quickly.

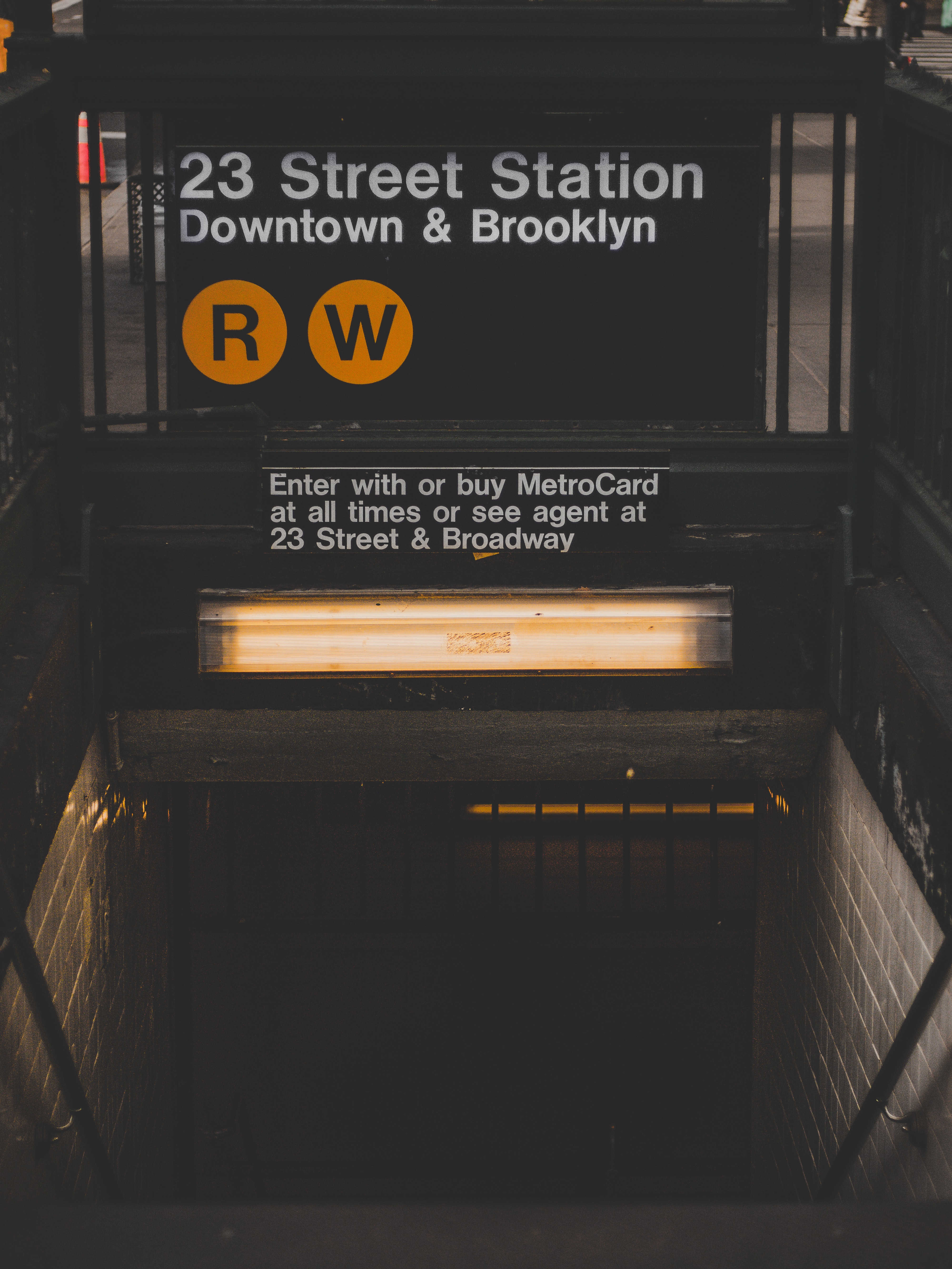

One of the key elements in decision making is experience. Experience comes from knowing the place you are in, and from having experienced things go wrong. Another one is timing. Having experienced and knowing when things are more chaotic around you, during the commute or any other daily activity, gives you the chance to plan ahead and have the baselines ready.

Finally, decision making comes down to knowing what you can and cannot control, flowing with the situation, and having the ability to adapt. A decision you made doesn’t have to set a course you can’t reverse or change. As the situation unfolds, a decision you made a second ago might need to be reconsidered, and a new decision needs to be made. You have to use an open and quick mind to quickly search for a past experience, combine what you have in front of you, and make a decision. Tools like the OODA Loop can help you with this. Yes, this is where training comes into the picture. The more you practice under stressful situations, the more you’ll experience things going wrong, and this in turn will build your ability to make better decisions.

How you practice this is, well, a topic for a full article or even a book, but the best you can do is to pay attention during your commute, see things - good and bad - unfolding in front of you and visualize how you’d react to each one of them.

So, how do you make better decisions? Create a baselines and guardrails that can help you quickly understand when something is not right and what you’ll do about it, and then practice. Stress inoculation is a good friend.

Stay light, stay aware, stay safe.